About the Book

With the experience I have with this book (I’ve partially read it up to three to four times before formally deciding to read it fully and take notes on it), I think it’s a fundamental book that should be introduced to everyone. It lays out a solid foundation (one that goes against the grain of romanticism) for people to use as an emotional base. The term “emotional base” in this sense is something upon which humans could base their actions and decisions in life – particularly on matters that pertain to emotions (love, pain, grief, etc).

review

Although this book was thought-provoking from the outset, a few of its passages were repetitive. Sometimes, I would look away from the book and outright disagree with what I’ve just read.

Some parts of the prose were beautiful – a few chapters, sentences, and whatnot – but a select few are also blithely presented through hasty generalizations and unsubstantiated arguments.

Nonetheless, it was a satisfying read. I’m always looking forward to a book that lets me think more deeply about and/or re-think my opinions.

I don’t want to undermine the lessons I’ve gotten from the book, so I’m giving it 3 stars. It’s not the best, not the worst – just OK… but important.

highlights and notes

Introduction

We are left to find our own path around our unfeasibly complicated minds – a move as striking(and as wise) as suggesting that each generation should rediscover the laws of physics by themselves.

- Highlight (blue) page: 32

It is implied in this paragraph that honing our emotional skills is just as important as sharpening our intellectual capabilities.

- Note page: 34

The results of a Romantic philosophy are everywhere to see: exponential progress in the material and technological fields combined with perplexing stasis in the psychological one.

- Highlight (blue) page: 40

We have the technology of an advanced civilization balancing precariously on an emotional base that has not developed much since we dwelt in caves. We have the appetites and destructive furies of primitive primates who have come into possession of thermonuclear warheads.

- Highlight (blue) page: 42

The evolution of our emotions lag behind the evolution of our technologies – our primitive instincts take over the best of us because we are, in some sense, built that way, whereas technology improves at an unprecedented state, arguably every day.

- Note page: 44

We are all astonishingly capable of messing up our lives, whatever the prestige of our university degrees, and are never beyond making a sincere contribution, however unorthodox our qualifications.

- Highlight (blue) page: 48

The plays of Sophocles and Racine, the paintings of Botticelli and Rembrandt, the literature of Goethe and Baudelaire, the philosophy of Plato and Schopenhauer, the musical compositions of Liszt and Wagner: these would provide the raw material from which an adequate replacement for the guidance and consolation of the faiths could be formulated.

- Highlight (blue) page: 68

Michel de Montaigne’s Essays(1580) amounted to a practical compendium of advice on helping us to know our fickle minds, find purpose, connect meaningfully with others and achieve intervals of composure and acceptance.

- Highlight (pink) page: 97

Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time(1913) was, with equally practical ambition, a self-help book intent on delineating the most sincere and intelligent way that we might stop squandering and start to appreciate our too brief lives.

- Highlight (pink) page: 98

As children, when someone asked our age, we might have said, ‘I’m four’, and added, with great solemnity, ‘and a half’. We didn’t want anyone to think we were only four. We had travelled so far in those few months, but then again we were modest enough to sense that the huge dignity of turning five was still quite far away. In other words, as children, we were hugely conscious of the rapidity and intensity of human development and wanted clearly to signal to others and ourselves what dramatic metamorphoses we might undergo in the course of our ordinary days and nights. It would nowadays sound comic or a touch mad for an adult to say proudly, ‘I’m twenty-five and a half’ or ‘forty-one and three-quarters’ – because, without particularly noticing, we’ve drifted away from the notion that adults, too, are capable of evolutions. Once we’re past eighteen or so, our progress is still monitored but it is envisaged in different terms: it is cast in the language of material and professional advancement. The focus is on what grades have been achieved, what career has been chosen and what progress has been made in the corporate hierarchy. Development becomes largely synonymous with promotion. But emotional growth still continues. There won’t be a simple outward measure: we’re no taller, we’ve not boosted our seniority at work and we’ve received no new title to confirm our matriculation to the world. Yet there have been changes nevertheless. We may, over two sleepless nights, have entirely rethought our attitude to envy or come to an important insight about the way we behave when someone compliments us. We may have made a momentous step in self-forgiveness or resolved one of the riddles of a romantic relationship. These quiet but very real milestones don’t get marked. We’re not given a cake or a present to mark the moment of growth. We’re not congratulated by others or viewed with enhanced respect. No one cares or even knows how caring might work. But inside, privately, we might harbour a muffled hope that some of our evolutions will be properly prized. In an ideal world, we might have in our possession maps of emotional progress against which we could plot our faltering advance towards more sustained maturity. We might conceive of our inner developments as trips around a region, each one with distinct landmarks and staging posts, and as significant in their way as the cities of Renaissance Italy or the beauty spots on the Pacific Highway – and which we might be equally proud to have reached and come to understand our way around.

- Highlight (blue) page: 105

Improvement doesn’t always have to be measured. Change, in some cases(especially in adult lives), signals improvement – and so we should recognize our seemingly infinitesmal progress. Those improvements matter.

- Note page: 124

the education system assumes that once we understand something, it will stick in our minds for as long as we need it to. These minds are envisaged as a little like computer hard drives: unless violently knocked, they will hold on to data for the long term. This is why we might imagine that education could stop at the age of twenty-two, once the important things have been imbibed.

- Highlight (blue) page: 129

we forget almost everything. Our memories are sieves, not robust buckets. What seemed a convincing call to action at 8 a.m. will be nothing more than a dim recollection by midday and an indecipherable contrail in our cloudy minds by evening.

- Highlight (blue) page: 136

It was the philosophers of ancient Greece who first identified these problems and described the structural deficiencies of our minds with a special term. They proposed that we suffer from akrasia, commonly translated as ‘weakness of will’, a habit of not listening to what we accept should be heard and a failure to act upon what we know is right. It is because of akrasia that crucial information is frequently lodged in our minds without being active in them and it is because of akrasia that we often both understand what we should do and resolutely omit to do it.

- Highlight (blue) page: 138

The Madonna of the Book was not seeking idly to charm the eye but to impress upon viewers the value of maternal care, sacrifice and sorrowful contemplation. Expressed in blunt words, the instruction would – Ficino and Botticelli knew – have gone nowhere. It needed, in order to carry deep into our minds, the help of an azure sky, the dance of a rich gold filigree, an adorable child and an exceptionally tender maternal figure; ideas, however noble, tend to require a little help from beauty.

- Highlight (blue) page: 159

Unlike standard modern education, ritual doesn’t aim to teach us anything new; it wants to lend compelling form to what we believe we already know. It wants to turn our theoretical allegiances into habits. It is, not coincidentally, also religions that have been especially active in the design and propagation of rituals. It is they that have created occasions at which to tug our minds back to honouring the seasons, remembering the dead, looking inside ourselves, focusing on the passage of time, empathizing with strangers, forgiving transgressions or apologizing for misdeeds. They have put dates in our diaries to take our minds back to our most sincere commitments.

- Highlight (blue) page: 167

Buddhism described life itself as a vale of suffering; the Greeks insisted on the tragic structure of every human project; Christianity interpreted each of us as being marked by a divine curse.

- Highlight (pink) page: 195

First formulated by the philosopher St Augustine in the closing days of the Roman Empire, ‘original sin’ generously insisted that humanity was intrinsically, rather than accidentally, flawed. That we suffer, feel lost and isolated, are racked with worry, miss our own talents, refuse love, lack empathy, sulk, obsess and hate: these are not merely personal flaws, but constitute the essence of the human animal. We are broken creatures and have been since our expulsion from Eden, damned – to use the resonant Latin phrase – by peccatum originale.

- Highlight (blue) page: 197

This resonates with an idea I first encountered from Jordan Peterson: “All of humanity is pain, sickness, and death.” It’s a humbling concept that I, even up to this date, believe and uphold. If something bad happens – I just say, “It is what it is,” but what I really mean is that we are all damned, and are bound to be damned, in some way or another.

- Note page: 201

There can wisely be no ‘solutions’, no self-help, of a kind that removes problems altogether. What we can aim for, at best, is consolation – a word tellingly lacking in glamour. To believe in consolation means giving up on cures; it means accepting that life is a hospice rather than a hospital, but one we’d like to render as comfortable, as interesting and as kind as possible.

- Highlight (blue) page: 207

Understanding does not magically remove the pain but it has the power to reduce a range of secondary aggravations and fears. At least we know what is racking us and why. Our worst fears are held in check, and tears may be turned into bitter knowledge.

- Highlight (blue) page: 211

there is solace in the discovery that everyone else is, in private, of course as bewildered and regretful as we are.

- Highlight (blue) page: 213

Schadenfreude,

- Highlight (orange) page: 214

Pleasure derived by someone from another person’s misfortune.

- Note page: 215

The melancholy know that many of the things we most want are in tragic conflict: to feel secure and yet to be free; to have money and yet not to have to be beholden to others; to be in close-knit communities and yet not to be stifled by the expectations and demands of society; to explore the world and yet to put down deep roots; to fulfil the demands of our appetites for food, sex and sloth and yet stay thin, sober, faithful and fit.

- Highlight (yellow) page: 233

redolent

- Highlight (yellow) page: 237

Suggestive of.

- Note page: 237

There are melancholy landscapes and melancholy pieces of music, melancholy poems and melancholy times of day. In them, we find echoes of our own griefs, returned back to us without some of the personal associations that, when they first struck us, made them particularly agonizing.

- Highlight (blue) page: 238

We should gracefully acknowledge how much of what nourishes and guides us, how much of what we should be hearing is astonishingly, almost humiliatingly, simple in structure.

- Highlight (blue) page: 255

I : Self

We are not a fixed destination, but an eternally mobile, boundless, unfocused, vaporous spectre whose full nature can only be retrospectively deduced from painfully recollected glimpses and opaque hints.

- Highlight (yellow)

A successful search for self-knowledge may furnish us not with a set of newly mined rock-solid certainties, but with an admission of how little we do – and ever can – properly know ourselves.

- Highlight (yellow)

For the sceptics, understanding that we may be repeatedly hoodwinked by our own minds is the start of the only kind of intelligence of which we are ever capable; just as we are never as foolish as when we fail to suspect we might be so.

- Highlight (yellow)

Maturity involves accepting with good grace that we are all – like marionettes – manipulated by the past. And, when we can manage it, it may also require that we develop our capacity to judge and act in the ambiguous here and now with somewhat greater fairness and neutrality.

- Highlight (yellow)

Almost universally, without anyone intending this to happen, somewhere in our childhood our trajectory towards emotional maturity can be counted upon to have been impeded. Even if we were sensitively cared for and lovingly handled, even if parental figures approached their tasks with the highest care and commitment, we can be counted upon not to have passed through our young years without sustaining some form of deep psychological injury – what we can term a set of ‘primal wounds’.

- Highlight (blue)

In the tragic tales of the ancient Greeks, it is not enormous errors and slips that unleash drama but the tiniest, most innocent of mistakes.

- Highlight (blue)

It may be the work of decades to develop a wiser power to feel sad about, rather than eternally responsible for, those we love but cannot change. And perhaps, at points, in the interests of self-preservation, to move on.

- Highlight (blue)

“You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink.""Don’t cast pearl before swine.”

- Note

We may be well into middle age before we can shed our first impulses to explode at or flee from those who misunderstand our needs, and more carefully and serenely strive to explain them instead.

- Highlight (blue)

We are judged on the behaviours that our wounds inspire, rather than on the wounds themselves.

- Highlight (blue)

To any grown-up, it is immediately obvious that a three-year-old having a tantrum in a hotel restaurant is irritating, theatrical and bad-mannered. But that is chiefly because we lack the encouragement or empathetic energy to try to recreate the strange inner world of a small person in which she might feel monumentally tired and bewildered, fearful that an unfamiliar dish was going to be forced on her, or lonely and humiliated by being the smallest person in a large and lugubrious dining room, far away from Lanky, the stuffed rabbit left by mistake on the floor in the room upstairs.

- Highlight (blue)

One night as I was in a family dinner at a local Filipino restaurant, the daughter of my cousin wailed. It seemed as if she didn’t like being touched by my cousin’s nanny – but to a person who hasn’t read The School of Life, it may have seemed as if the child just had an ‘attitude’ or a certain degree of recalcitrance.

- Note

We keep away from ourselves because so much of what we could discover threatens to be agony.

- Highlight (blue)

What properly indicates addiction is not what someone is doing, but their way of doing it, and in particular their desire to avoid any encounter with certain sides of themselves. We are addicts whenever we develop a manic reliance on something, anything, to keep our darker and more unsettling feelings at bay.

- Highlight (blue)

We lie by attacking and denigrating what we love but haven’t managed to get. We dismiss the people we once wanted as friends, the careers we hoped at the start one day to have, the lives we tried to emulate. We reconfigure what a desired but painfully elusive goal meant to us in the hope of not having to register its loss properly.

- Highlight (blue)

We write dense books on the role of government bonds in the Napoleonic Wars or publish extensively on Chaucer’s influence on the mid-nineteenth-century Japanese novel. We secure degrees from institutes of advanced study or positions on editorial boards of scientific journals. Our minds are crammed with arcane data. We can wittily inform a dining table of guests who wrote the Enchiridion(Epictetus) or describe the life and times of Dōgen(the founder of Zen Buddhism). But we don’t remember very much at all about how life was long ago, back in the old house, when our father left, our mother stopped smiling and our trust broke in pieces.

- Highlight (blue)

We lean on the glamour of being learned to limit all that we might really need to learn about.

- Highlight (blue)

We use the practical mood of Monday morning 9 a.m. to ward off the complex insights of 3.a.m. the previous night, when the entire fabric of our existence came into question.

- Highlight (blue)

We need to tell ourselves a little more of the truth because we pay too high a price for our concealments.

- Highlight (blue)

In the arena of self-knowledge, psychotherapy may be the single most useful intervention of the last 200 years. It is a tool and, like all tools, it finds its purpose in helping us to overcome an inborn weakness and to extend our capacities beyond those originally gifted to us by nature. It is, in this sense, not metaphysically different from a bucket, which remedies the problem of trying to hold water in our palms, or a knife, which makes up for the bluntness of our teeth.

- Highlight (yellow)

In response to our isolation, we are often told about the importance of friends. But we know that the tacit contract of any friendship is that we will not bother the incumbent with more than a fraction of our madness. A lover is another solution, but it is – likewise – not in the remit of even a highly patient partner to delve into, and accept, more than a modest share of what we are.

- Highlight (yellow)

They have close-up experience of the greatest traumas – incest and rape, suicide and depression – as well as the smaller pains and paradoxes: a longing provoked by a glance at a person in a library that took up the better part of twenty years, an otherwise gentle soul who broke a door, or a handsome, athletic man who can no longer perform sexually.

- Highlight (yellow)

They know that inside every adult there remains a child who is confused, angry, hurt and longing to have their say and their reality recognized.

- Highlight (yellow)

In a sufficiently calm, reassuring and interested environment, we can look at areas of vulnerability we are otherwise too burdened to tackle. We can dare to think that perhaps we were wrong or that we have been angry for long enough; that it might be best to outgrow our justifications or halt our compulsion to charm others indiscriminately.

- Highlight (yellow)

For all the glamour of the solitary seer, thinking usually happens best in tandem.

- Highlight (yellow)

I kind of disagree with this but I do not know the precise reason for it.

- Note

bathetic

- Highlight (yellow)

We need to strive for what we can call an emotional understanding of the past, as opposed to a top-down, abbreviated, intellectual one.

- Highlight (yellow)

We need not only to know that we had a difficult relationship with our father, but to relive the sorrow as if it were happening to us today. We need to be back in his book-lined study when we were not more than six; we need to remember the light coming in from the garden, the corduroy trousers we were wearing, the sound of our father’s voice as it reached its pitch of heightened anxiety, the rage he flew into because we had not met his expectations, the tears that ran down our cheeks, the shouting that followed us as we fled out into the corridor, the feeling that we wanted to die and that everything good was destroyed. We need the novel, not the essay.

- Highlight (yellow)

the difference between knowing, in an abstract way, that our mother wasn’t much focused on us when we were little and reconnecting with the desolate feelings we had when we tried to share certain of our needs with her.

- Highlight (yellow)

It’s only when we’re properly in touch with our feelings that we can correct them with the help of our more mature faculties – and thereby address the real troubles of our adult lives.

- Highlight (yellow)

intellectual people can have a particularly tricky time in therapy. They get interested in the ideas. But they don’t so easily recreate and exhibit the pains and distresses of their earlier, less sophisticated selves, though it’s actually these parts of who we all are that need to be encountered, listened to and – perhaps for the first time – comforted and reassured.

- Highlight (yellow)

The therapist will gently point out that we’re reacting as if we had been attacked, when they only asked a question; they might draw our attention to how readily we seem to want to tell them impressive things about our finances(yet they like us anyway) or how we seem to rush to agree with them when they’re only trying out an idea which they themselves are not very sure of(we could dare to disagree and not upset them).

- Highlight (yellow)

Through a relationship with someone who will not respond as ordinary people will, who will not shout at us, complain, say nothing or run away – in other words, with a proper grown-up – we can be helped to understand our immaturities.

- Highlight (yellow)

An inner voice was always an outer voice that we have – imperceptibly – made our own. We’ve absorbed the tone of a kind and gentle caregiver who liked to laugh indulgently at our foibles and had endearing names for us. Or else we have taken in the voice of a harassed or angry parent, never satisfied with anything we achieved and full of rage and contempt.

- Highlight (blue)

We need to become better friends to ourselves. The idea sounds odd, initially, because we naturally imagine a friend as someone else, not as a part of our own mind. But there is value in the concept because of the extent to which we know how to treat our own friends with a sympathy and imagination that we don’t apply to ourselves. If a friend is in trouble our first instinct is rarely to tell them that they are fundamentally a failure. If a friend complains that their partner isn’t very warm to them, we don’t tell them that they are getting what they deserve. In friendship, we know instinctively how to deploy strategies of wisdom and consolation that we stubbornly refuse to apply to ourselves.

- Highlight (blue)

People don’t just sometimes fail. Everyone fails, as a rule; it’s just we seldom know the details.

- Highlight (blue)

furtive

- Highlight (blue)

adjective. attempting to avoid notice or attention.

- Note

The people who caused our primal wounds almost invariably didn’t mean to do so; they were themselves hurt and struggling to endure. We can develop a sad but realistic picture of a world in which sorrows and anxieties are blindly passed down the generations. The insight isn’t only true with regard to experience; holding it in mind will mean there is less to fear. Those who wounded us were not superior, impressive beings who knew our special weaknesses and justly targeted them. They were themselves highly frantic, damaged creatures trying their best to cope with the litany of private sorrows to which every life condemns us.

- Highlight (yellow)

Noun. A tedious recital or repetitive series.

- Note

noun. a tedious recital or repetitive series.

- Note

The first asks what we might be anxious about right now.

- Highlight (yellow)

what am I upset about right now?

- Highlight (yellow)

What we call depression is in fact sadness and anger that have for too long not been paid the attention they deserve.

- Highlight (yellow)

what am I ambitious and excited about right now?

- Highlight (yellow)

inchoate

- Highlight (yellow)

Nascent

- Note

In a poem written in 1908, the German poet Rilke described coming across an ancient statue of the Greek god Apollo. It had had its arms knocked off at the shoulders but still manifested the intelligence and dignity of the culture that had produced it. Rilke felt an unclear excitement, and as he meditated upon and investigated his response, he concluded that the statue was sending him a message, which he announced in the final, dramatic line of his short poem, ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’: Du mußt dein Leben ändern. [You must change your life.]

- Highlight (yellow)

abstruse

- Highlight (yellow)

Difficult to understand.

- Note

Novels, films and songs should constantly be defining and evoking states of mind we thought we were alone in experiencing but that belong to the typical lot of humankind. We should put down the average novel wondering – with relief – how the novelist had come to know so much about us. We should begin to understand that an average stranger is always far more likely to be as we know we are – with all our quirks, fragilities, compulsions and surprising aspects – than they are to resemble the apparently ‘normal’ person their exterior implies.

- Highlight (yellow)

We need a broader, more reassuring sense of what is common. Of course it is normal to be envious, crude, sexual, weak, in need, childlike, grandiose, terrified and furious. It is normal to desire random adventures even within loving, committed unions. It is normal to be hurt by ‘small’ signs of rejection, and to be made quickly very insecure by any evidence of neglect by a partner. It is normal to harbour hopes for ourselves professionally that go far beyond what we have currently been able to achieve. It is normal to envy other people, many times a day, to be very upset by any kind of criticism of our work or performance, and to be so sad we regularly daydream of flight or a premature end.

- Highlight (yellow)

A breakdown is not merely a random piece of madness or malfunction, it is a very real – albeit very inarticulate – bid for health and self-knowledge. It is an attempt by one part of our mind to force the other into a process of growth, self-understanding and self-development which it has hitherto refused to undertake.

- Highlight (yellow)

A breakdown isn’t just a pain, though it is that too of course; it is an extraordinary opportunity to learn.

- Highlight (yellow)

reclusive,

- Highlight (yellow)

Solitary - avoing the company of other people.

- Note

dislodge

- Highlight (yellow)

Remove from a fixed position.

- Note

II : Others

Charity involves offering someone something that they may not entirely deserve and that it is a long way beyond the call of duty for us to provide: sympathy.

- Highlight (yellow)

We need charity, but not of the usual kind; we need what we might term a ‘charity of interpretation’: that is, we require an uncommonly generous assessment of our idiocy, weakness, eccentricity or deceit.

- Highlight (yellow)

onlookers

- Highlight (yellow)

Non-participating observer.

- Note

In cases of financial charity, the gifts tend to go in one direction only, from the rich to the poor. Those who give may be generous, but they tend to experience only one side of the equation, remaining for all their lives the donor rather than the recipient. They can be reasonably sure that they won’t ever be in material need, which is what can lend a somewhat unimaginative or aloof tone to their generosity. But when it comes to the gift of charitable interpretation, none of us is ever committedly beyond need. Such is our proclivity for error and our vulnerability to reversals of fortune, we are all on the verge of needing someone to come to our imaginative aid.

- Highlight (yellow)

We must be kind in the sense not only of being touched by the remote material suffering of strangers, but also of being ready to do more than condemn and hate the sinful around us, hopeful that we too may be accorded a tolerable degree of sympathy in our forthcoming hour of failure and shame.

- Highlight (yellow)

The great Greek tragedians – Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles – recounted stories of essentially respectable, intelligent and honest men and women who, on account of a minor and understandable error or omission, unleashed catastrophe and ended up in a very short time dead or ruined.

- Highlight (yellow)

The most shocking events can befall the more or less innocent or the only averagely muddled and weak. We do not inhabit a properly moral universe: disaster at points befalls those who could not have expected it to be a fair outcome, given what they did. The Greeks were the originators of a remarkable, appalling and still-too-seldom-accepted possibility that failure is not reserved simply for the evil.

- Highlight (yellow)

travails

- Highlight (yellow)

Painful or laborious effort.

- Note

THE WEAKNESS OF STRENGTH

- Highlight (yellow)

Refer to this in your mini-essay.

- Note

We should in our most impatient and intemperate moments strive to hold on to the concept of the weakness of strength. This dictates that we should interpret people’s weaknesses as the inevitable downside of certain merits that drew us to them, and from which we will benefit at other points(even if none of these benefits are apparent right now). What we’re seeing are not their faults, pure and simple, but rather the shadow side of things that are genuinely good about them. If we were to write down a list of strengths and then of weaknesses, we’d find that almost everything on the positive side of the ledger could be connected up with something on the negative.

- Highlight (yellow)

assiduously

- Highlight (yellow)

Showing great care and perseverance.

- Note

florid,

- Highlight (yellow)

Really elaborate or immensely complex

- Note

forthwith,

- Highlight (yellow)

Immdiately.

- Note

atonement

- Highlight (yellow)

Reparation for a wrong or injury.

- Note

Pure evil is seldom at work. Almost all our worst moments can be traced back to an unexotic, bathetic, temptingly neglected ingredient: pain.

- Highlight (yellow)

A traditional folk tale known as ‘Androcles and the Lion’, originally recounted by the ancient Roman philosopher Aulus Gellius, tells of a Barbary lion – nine feet long with a splendid dark mane – who lived in the forested foothills of the Atlas Mountains(in what is today Algeria). Usually he kept far from human settlements, but one year, in spring, he started approaching the villages at night, roaring and snarling menacingly in the darkness. The villagers were terrified. They put extra guards on the gates and sent out heavily armed hunting parties to try to slaughter the beast. It happened around this time that a shepherd boy named Androcles followed his sheep far into the high mountain pastures. One evening, he sought shelter in a cave. He had just lit a candle and was setting out his blanket when he saw the ferocious animal glaring at him from a corner. At first he was terrified. It seemed as if the angry lion might be about to pounce and rip him to pieces. But then Androcles noticed something: there was a thorn deeply embedded in one of the lion’s front paws and a huge tear was running down his noble face. The creature wasn’t murderous, he was in agony. So instead of trying to flee or defend himself with his dagger, the boy’s fear turned to pity. Androcles approached the lion, stroked his mane and gently, reassuringly extracted the thorn from the paw, wrapping it in a strip of cloth torn from his own blanket. The lion licked the boy’s hand and became his friend for life.

- Highlight (yellow)

We resent others with unhelpful speed when we lack the will to consider the origins of their behaviour.

- Highlight (yellow)

People are bad, always, because they are in difficulty. They slander, gossip, denigrate and growl because they are not in a good place. Though they may seem strong, though their attacks can place them in an apparently dominant role, their ill intentions are all the proof we require to know as a certainty that they are not well. Contented people have no need to hurt others.

- Highlight (yellow)

One has to feel very small in order to belittle.

- Highlight (yellow)

We, who have no wish to hurt, are in fact the stronger party; we, who have no wish to diminish others, are truly powerful. We can move from helpless victims to imaginative witnesses of justice.

- Highlight (yellow)

In the late eighteenth century, an ideal of Romantic anti-politeness emerged, largely driven forward by the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who powerfully redescribed politeness in terms of inauthenticity, servility and deceit. What was important for Rousseau was never to hide or moderate emotions and thoughts, but to remain – at all times – fundamentally true to oneself.

- Highlight (yellow)

Frank people believe in the importance of expressing themselves honestly principally because they trust that what they happen to think and feel will always prove fundamentally acceptable to the world. Their true sentiments and opinions may, when voiced, be bracing of course, but no worse. Frank types assume that what is honestly avowed cannot really ever be vindictive, disgusting, tedious or cruel. In this sense, the frank person sees themselves a little in the way we typically see small children: as blessed by an original and innate goodness.

- Highlight (yellow)

infelicities

- Highlight (yellow)

An inappropriate remark.

- Note

attenuate

- Highlight (yellow)

Reduce the effect of or value

- Note

The polite person will be drawn to deploying softening, tentative language and holding back on criticism wherever possible. They will suggest that an idea might not be quite right. They will say that a project is attractive but that it could be interesting to look at alternatives as well. They will concede that an intellectual opponent may well have a point. They aren’t just lying or dodging tough decisions. Their behaviour is symptomatic of a nuanced and intelligent belief that few ideas are totally without merit, no proposals are 100 per cent wrong and almost no one is entirely foolish. They work with a conception of reality in which good and bad are deviously entangled and in which bits of the truth are always showing up in unfamiliar guises in unexpected people. Their politeness is a logical, careful response to the complexity they identify in themselves and in the world.

- Highlight (yellow)

touchy

- Highlight (yellow)

Oversensitive or irritable.

- Note

Diplomacy is the art of advancing an idea or a cause without unnecessarily inflaming passions or unleashing a catastrophe. It involves an understanding of the many facets of human nature that can undermine agreement and stoke conflict, and a commitment to unpicking these with foresight and grace.

- Highlight (yellow)

Another trait of the diplomat is to be serene in the face of obviously bad behaviour: a sudden loss of temper, a wild accusation, a very mean remark. They don’t take it personally, even when they may be the target of rage. They reach instinctively for reasonable explanations and have clearly in their minds the better moments of a currently frantic but essentially lovable person. They know themselves well enough to understand that abandonments of perspective are both hugely normal and usually indicative of nothing much beyond passing despair or exhaustion.

- Highlight (yellow)

febrile

- Highlight (yellow)

Having symptoms of a fever.

- Note

The person who bangs a fist on the table or announces extravagant opinions is most likely to be simply rather worried, frightened, hungry or just very enthusiastic: conditions that should rightly invite sympathy rather than disgust.

- Highlight (yellow)

We mistake leaving some room for hope for kindness. But true niceness does not mean seeming nice, it means helping the people we are going to disappoint to adjust as best they can to reality.

- Highlight (yellow)

Our shy episodes are rooted in an experience of difference. They, the ones who have sparked our intimidation, are all women or all men, all from the north or all from the south, all rich or all poor, all confident people or all winners. And we are not – and therefore have nothing whatever to say. To dislodge us from our silence, we can think of ourselves as each possessing two different kinds of identities. Our local identity comprises our age, gender, skin colour, sexuality, social background, wealth, career, religion and personality type. But beyond this, we also have a universal identity, made up of what we have in common with every other member of the species: we all have problematic families, have all been disappointed, have all been idiotic, have all loved, have all had problems around money, all have anxieties – and will all, when we are pricked, start to bleed.

- Highlight (yellow)

The last line is Shylock’s from his famous impassioned outburst in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, one of the most beautiful celebrations of universal identity ever delivered: ‘I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die?’

- Highlight (yellow)

Shakespeare had read and absorbed the writings of the Roman playwright Terence, who is remembered for one very famous declaration: ‘Homo sum, humani nil a me alienum puto’(‘I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me’).

- Highlight (yellow)

pathos,

- Highlight (yellow)

A quality that evokes sadness.

- Note

We have to realize that whether or not the other person likes us is going to depend on what we do, not – mystically – what we by nature ‘are’, and that we have the agency to do rather a lot of things.

- Highlight (yellow)

It is sad enough when two people dislike each other. It is even sadder when two people fail to connect because both parties defensively but falsely guess that the other doesn’t like them – and yet, out of low self-worth, takes no risk whatever to alter the situation. We should stop worrying quite so much whether or not people like us, and make that far more interesting and socially useful move: concentrate on showing that we like them.

- Highlight (yellow)

perturbed

- Highlight (yellow)

Anxious or unsettled.

- Note

True adulthood begins with a firmer hold on the notion that the solid and dignified person will, behind the scenes, almost certainly be craving something quite ordinary – something as unelevated and as human as a hug, a cry or a glass of milk.

- Highlight (yellow)

The English critic Cyril Connolly captured the phenomenon in relation to weight: ‘Imprisoned in every fat man, a thin man is wildly signalling to be let out.’ The image is ripe for extension: inside every bitter cynic, a bruised optimist is looking for an opening. Inside the rule-bound, precise, formal person, a playful, silly self is hoping for release. Inside the important person admired for their status is a child who wants to be liked for themselves.

- Highlight (yellow)

One of the largest questions we can ask ourselves, one which directly points us to the areas of our nature we should like to reform, is: what would I like to be teased about?

- Highlight (yellow)

Our civilization is full of great books on how to speak – Cicero’s On the Orator and Aristotle’s Rhetoric were two of the greatest in the ancient world – but sadly no one has ever written a book called The Listener.

- Highlight (yellow)

egging

- Highlight (pink)

encourage something foolish

- Note

muddled

- Highlight (blue)

not in order

- Note

indelible

- Highlight (yellow)

Of ink making marks that cannot be removed.

- Note

We might be at a drinks party where we mention how much we enjoyed reading a very funny, very scathing review of a new book. Then someone whispers to us that one of the people we are addressing is the book’s author. Or we were instrumental in having a particular colleague fired – and now they are at the next table in the little restaurant and have looked up and noticed us. Or our partner left their devastated spouse for us a year ago and now this spouse is next to us in line at the airport, waiting to board the same flight. Or we notice a heavily pregnant woman standing near us on a train and offer her our seat. And she thanks us and, with a wan smile, specifies that she isn’t pregnant at all. We have not set out to be evil or idiotic – the book really was very badly written, our colleague was truly not suited for the role, our partner is much happier with us, the passenger did legitimately look close to a due date – and yet we have unleashed what is without question a disaster.

- Highlight (yellow)

Witheringly scornful; severely critical.

- Note

Pale appearance.

- Note

blather.

- Highlight (yellow)

Blabber.

- Note

pretence

- Highlight (yellow)

A false display of feelings.

- Note

Our name will always be a byword for insensitivity and idiocy in certain circles and we will have to carry the pain in our hearts until the end. We will be wincing decades from now at the irredeemable proof of a stubborn strain of cowardice and foolishness within us.

- Highlight (yellow)

blithe

- Highlight (yellow)

Casual and cheerful indifference - negative connotation.

- Note

presumptuous,

- Highlight (yellow)

Someone failing to observe limits.

- Note

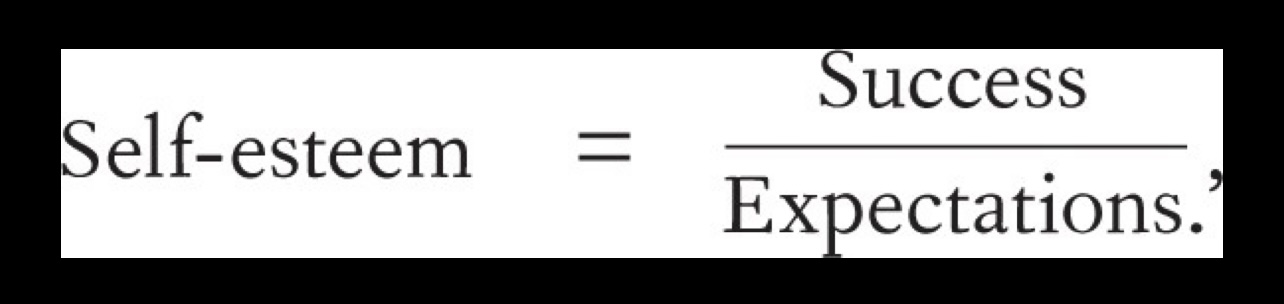

Our degree of satisfaction is critically dependent on our expectations. The greater our hopes, the greater the risks of rage, bitterness, disappointment and a sense of persecution.

- Highlight (yellow)

‘With no attempt there can be no failure; with no failure no humiliation. So our self-esteem in this world depends entirely on what we back ourselves to be and do,’ wrote the psychologist William James. ‘It is determined by the ratio of our actualities to our supposed potentialities … thus:

- Highlight (yellow)

adroitly

- Highlight (yellow)

Cleverly

- Note

However illogical rage can look, it is never right to dismiss it as merely beyond understanding or control. It operates according to a universal underlying rationale: we shout because we are hopeful.

- Highlight (yellow)

How badly we react to frustration is ultimately determined by what we think of as normal. We may be irritated that it is raining, but our pessimistic accommodation to the likelihood of its doing so means we are unlikely ever to respond to a downpour by screaming. Our annoyance is tempered by what we understand can be expected of existence.

- Highlight (yellow)

Our furies spring from events which violate a background sense of the rules of existence. And yet we too often have the wrong rules. We shout when we lose the house keys because we somehow believe in a world in which belongings never go astray. We lose our temper at being misunderstood by our partner because something has convinced us that we are not irredeemably alone. So we must learn to disappoint ourselves at leisure before events take us by surprise. We must be systematically inducted into the darkest realities – the stupidities of others, the ineluctable failings of technology, the eventual destruction of all that we cherish – while we are still capable of a relative measure of rational control.

- Highlight (yellow)

Irresistible or unavoidable.

- Note

mediatized

- Highlight (yellow)

Influenced by media

- Note

In her great novel Middlemarch, the nineteenth-century English writer George Eliot, a deeply self-aware but also painfully anxious figure, reflected on what it would be like if we were truly sensitive, open to the world and felt the implications of everything: ‘If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.’

- Highlight (yellow)

Clad

- Note

veneer

- Highlight (yellow)

Thin cover

- Note

exuberant

- Highlight (yellow)

Lively

- Note

Anxiety deserves greater dignity. It is not a sign of degeneracy, rather a kind of masterpiece of insight: a justifiable expression of our mysterious participation in a disordered, uncertain world.

- Highlight (yellow)

asphyxiated

- Highlight (yellow)

Choke

- Note

gregarious.

- Highlight (yellow)

Sociable

- Note

latent

- Highlight (yellow)

Existing but underdeveloped

- Note

We need to be alone because life among other people unfolds too quickly. The pace is relentless: the jokes, the insights, the excitements. There can sometimes be enough in five minutes of social life to take up an hour of analysis. It is a quirk of our minds that not every emotion that impacts us is at once fully acknowledged, understood or even – as it were – truly felt.

- Highlight (yellow)

After time among others, there are myriad sensations that exist in an ‘unprocessed’ form within us. Perhaps an idea that someone raised made us anxious, prompting inchoate impulses for changes in our lives. Perhaps an anecdote sparked off an envious ambition that is worth decoding and listening to in order to grow. Maybe someone subtly fired an aggressive dart at us and we haven’t had the chance to realize we are hurt. We need quiet to console ourselves by formulating an explanation of where the nastiness might have come from.

- Highlight (yellow)

Underdeveloped

- Note

reproach

- Highlight (yellow)

Address disaprovingly

- Note

The point of staring out of a window is, paradoxically, not to find out what is going on outside. It is, rather, an exercise in discovering the contents of our own minds. It is easy to imagine we know what we think, what we feel and what’s going on in our heads. But we rarely do entirely. There’s a huge amount of what makes us who we are that circulates unexplored and unused. Its potential lies untapped. It is shy and doesn’t emerge under the pressure of direct questioning. If we do it right, staring out of the window offers a way for us to be alert to the quieter suggestions and perspectives of our deeper selves.

- Highlight (yellow)

Plato suggested a metaphor for the mind: our ideas are like birds fluttering around in the aviary of our brains. But in order for the birds to settle, Plato understood that we need periods of purpose-free calm.

- Highlight (yellow)

Large cage for birds

- Note

drizzle.

- Highlight (yellow)

Light rain

- Note

overarching

- Highlight (yellow)

Ulterior

- Note

The potential of daydreaming isn’t recognized by societies obsessed with productivity. But some of our greatest insights come when we stop trying to be purposeful and instead respect the creative potential of reverie. Window daydreaming is a strategic rebellion against the excessive demands of immediate, but in the end insignificant, pressures in favour of the diffuse, but very serious, search for the wisdom of the unexplored deep self.

- Highlight (yellow)

Being pleasantly lost in thought.

- Note

There are many things we want desperately to avoid, which we will spend huge parts of our lives worrying about and which we will then bitterly resent when they force themselves upon us nevertheless.

- Highlight (yellow)

The idea of inevitability is central to the natural world: the deciduous tree has to shed it leaves when the temperature dips in autumn; the river must erode its banks; the cold front will deposit its rain; the tide has to rise and fall. The laws of nature are governed by forces nobody has chosen, no one can resist and which brook no exception.

- Highlight (yellow)

What we most fear can happen irrespective of our desires. But when we see frustration as a law of nature, we drain it of some of its sting and bitterness. We recognize that limitations are not in any way unique to us. In awesome, majestic scenes(the life of an elephant; the eruption of a volcano), nature moves us away from our habitual tendency to personalize and rail against our lot.

- Highlight (yellow)

At this moment, nature seems to be sending us a humbling message: the incidents of our lives are not terribly important. And yet, strangely, rather than being distressing, this sensation can be a source of immeasurable solace and calm.

- Highlight (yellow)

The encounter with the sublime undercuts the gradations of human status and makes everyone – at least for a time – look relatively unimpressive.

- Highlight (yellow)

respite

- Highlight (yellow)

A period of short rest.

- Note

eke

- Highlight (yellow)

Make a living with difficulty.

- Note

In the late eighteenth century, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant thought ‘the starry heavens above’ were the most sublime spectacle in nature and that contemplation of this transcendent sight could hugely assist us in coping with our travails. Although Kant was interested in the developing science of astronomy, he saw the field as primarily serving a major psychological purpose. Unfortunately, since then, the advances in astrophysics have become increasingly embarrassed around this aspect of the stars. It would seem deeply odd today if in a science class there were a special section not on the fact that Aldebaran is an orange-red giant star of spectral and luminosity type K5+III and that it is currently losing mass at a rate of(1–1.6) × 10-11 M⦿ yr-1 with a velocity of 30 km s-1 but rather on the ways in which the sight of stars can help us manage our emotional lives and relations with our families – even though knowing how to cope better with anxiety is in most lives a more urgent and important task than steering one’s rocket around the galaxies. Although we’ve made vast scientific progress since Kant’s time, we haven’t properly explored the potential of space as a source of wisdom, as opposed to a puzzle for astrophysicists to unpick.

- Highlight (yellow)

On an evening walk you look up and see the planets Venus and Jupiter shining in the darkening sky. As the dusk deepens you might see Andromeda and Aries. It’s a hint of the unimaginable extensions of space across the solar system, the galaxy, the cosmos. They were there, quietly revolving, their light streaming down, as spotted hyenas warily eyed a Stone Age settlement; and as Julius Caesar’s triremes set out after midnight to cross the Channel and reach the cliffs of England’s south coast at dawn. The sight has a calming effect because none of our troubles, disappointments or hopes have any relevance. Whatever happens to us, whatever we do, is of no consequence from the point of view of the universe.

- Highlight (yellow)

Our goal is to get clearer about where our own tantalizingly powerful yet always limited agency stops: where we will be left with no option but to bow to forces infinitely greater than our own.

- Highlight (yellow)

Tease about something unobtainable.

- Note

III : Relationships

bellwether

- Highlight (yellow)

The leading sheep of a flock.

- Note

intuit

- Highlight (yellow)

Understand by instinct.

- Note

underwriting

- Highlight (yellow)

Support

- Note

militate

- Highlight (yellow)

Be a powerful stopper for something. To stunt or hinder.

- Note

Far more than happiness, what motivates us in relationships is a search for familiarity – and what is familiar is not restricted to comfort, reassurance and tenderness; it may include feelings of abandonment, humiliation and neglect, which can form part of the list of paradoxical ingredients we need to refind in adult love.

- Highlight (yellow)

We might reject healthy, calm and nurturing candidates simply on the basis that they feel too right, too eerie in their unfamiliar kindness, and nowhere near as satisfying as a bully or an ingrate, who will torture us in just the way we need in order to feel we are in love.

- Highlight (yellow)

To get at the peculiar instincts which circulate powerfully in the less noticed corners of our brains, we might try to finish stub sentences that invite us to share what might charm or repel us in others: If someone shows me huge kindness and consideration, I … If someone isn’t entirely convinced by me, I … When someone tells me they really need me, I …

- Highlight (yellow)

wellsprings

- Highlight (yellow)

A bountiful source of something.

- Note

Rather than aim for a transformation in the types of people we are drawn to, it may be wiser to try to adjust how we respond and behave around the difficult characters whom our past mandates that we will find interesting.

- Highlight (yellow)

Our problems are often generated because we continue to respond to compelling people in the way we learned to behave as children around their templates. For instance, maybe we had a rather irate parent who often raised their voice. We loved them, but reacted by feeling that when they were angry we must be guilty. We got timid and humble. Now if a partner(to whom we are magnetically drawn) gets cross, we respond as squashed, browbeaten children: we sulk, we assume it’s our fault, we feel got at and yet deserving of criticism.

- Highlight (yellow)

Cowed

-

Note

-

Highlight (yellow)

The idea that one is in many ways an extremely difficult person to live around sounds, at first, improbable and even offensive. Yet fully understanding and readily and graciously admitting this possibility may be the surest way of making certain that one proves a somewhat endurable proposition. There are few people more deeply insufferable than those who don’t, at regular intervals, suspect they might be so.

- Highlight (yellow)

panoply

- Highlight (yellow)

An impressive collection.

- Note

it is impossible, on one’s own, to notice the extent of one’s power to madden. Our eccentric hours and reliance on work to ward off feelings of vulnerability can pass without comment when we fall singly into bed past one in the morning. Our peculiar eating habits lack reality without another pair of eyes to register our dismaying combinations.

- Highlight (yellow)

Everyone, seen close up, has an appalling amount wrong with them. The specifics vary hugely but the essential point is shared. It isn’t that a partner is too critical or unusually demanding. They are simply the bearer of inevitably awkward news. Asking anyone to be with us is in the end a peculiar request to make of someone we claim to care intensely about.

- Highlight (yellow)

We will have learned to love when our default response to unfortunate moments is not to feel aggrieved but to wonder what damaged aspects of a partner’s rocky past have been engaged.

- Highlight (yellow)

This reminds me of the ubiquitous Bible verse, “Love your enemies.”

- Note

We are ready for relationships not when we have encountered perfection, but when we have grown willing to give flaws the charitable interpretations they deserve.

- Highlight (yellow)

Our certainty that we might be happier with another person is founded on ignorance, the result of having been shielded from the worst and crazier dimensions of a new character’s personality – which we must accept are sure to be there, not because we know them in any detail, but because we know the human race.

- Highlight (yellow)

A charitable mindset doesn’t make it lovely to be confronted by the other’s troubles. But it strengthens our capacity to stick with them, because we see that their failings don’t make them unworthy of love, rather all the more urgently in need of it.

- Highlight (yellow)

Or else we become controlling – or what psychotherapists calls ‘anxious’. We grow suspicious, frantic and easily furious in the face of the ambiguous moments of love; catastrophe never feels too far away. A slightly distant mood must, we feel, be a harbinger of rejection; a somewhat non-reassuring moment is an almost certain prelude to the end. Our concern is touching, but our way of expressing it often less so, for it emerges indirectly as an attack rather than a plea. In the face of the other’s swiftly assumed unreliability, we complain administratively and try to control procedurally. We demand that they be back by a certain hour, we berate them for looking away from us for a moment, we force them to show us their commitment by putting them through an obstacle course of administrative chores. We get very angry rather than admit, with serenity, that we’re worried. We ward off our vulnerability by denigrating the person who eludes us. We pick up on their weaknesses and complain about their shortcomings. Anything rather than ask the question which so much disturbs us: do you still care? And yet, if this harsh, graceless behaviour could be truly understood for what it is, it would be revealed not as rejection or indifference, but as a strangely distorted – yet very real – plea for tenderness.

- Highlight (blue)

petulance,

- Highlight (yellow)

Childishly sulky or ill-tempered.

- Note

Lamentably,

- Highlight (yellow)

Deplorably bad

- Note

All of us change only when we have a sense that we are understood for the many reasons why change is so hard for us. We know, of course, that the bins need our attention, that we should strive to get to bed earlier and that we have been a disappointment. But we can’t bear to hear these lessons in an unsympathetic tone; we want – tricky children that we are – to be indulged for our ambivalence about becoming better people.

- Highlight (yellow)

Mixed feelings or contradictory ideas.

- Note

It is not the case that when we look at art or politics we are merely being kinky; rather that when we think we are merely being kinky we are in fact pursuing some very earnest and intelligible goals that are connected with a raft of other, higher aspirations.

- Highlight (yellow)

The thrill of oral sex is connected to a brief, magnificent reversal of all our internalized taboos. We no longer have to feel ashamed or guilty. The act may be physical, but the ecstasy is in essence an emotional relief that our secret and in subjective ways ‘bad’ sides have been witnessed and enthusiastically endorsed by another.

- Highlight (yellow)

Anal play would lose much of its capacity to delight if the anus were no more ‘dirty’ than a forehead or a shin; the pleasure is dependent on another human letting us do something avowedly filthy with and for them, and upon the implication that this is something they would never do with a person they cared little about. It is exactly the feeling that something is wrong, perverse or obscene that makes the mutual agreement to try it so great a mark of trust.

- Highlight (yellow)

We would be wise to begin studying the issue through the lens of perhaps the greatest novel of the twentieth century, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. In the first volume, Swann’s Way, Proust’s unnamed narrator, then a young teenager, is taking a walk near his grandmother’s house in the French countryside. As he passes a building at the edge of the village, he notices, in an upper bedroom, a woman, Mademoiselle Vinteuil, making love to a female friend. He is mesmerized and climbs a little hill for a better view. There he sees something even more surprising unfolding: Mademoiselle Vinteuil has positioned a photograph of her dead father on the bedside table and is encouraging her lesbian lover to spit on the image as they have sex, this gesture proving extremely exciting to them both. Early readers of Proust’s novel were puzzled by and heavily critical of this scene of erotic defilement. What was this revolting episode doing in an otherwise gracious and beautiful love story, filled with tender evocation of riverbanks, trees and domestic life? Proust’s editor wanted to cut the scene, but the novelist insisted on retaining it, asking the editor to understand its importance within his overarching philosophy of love.

- Highlight (yellow)

Proust’s argument is that defilement during sex isn’t what it seems. Ostensibly, it’s about violence, hatred, meanness and a lack of respect. But for Proust, it symbolizes a longing to be properly oneself in the presence of another human being, and to be loved and accepted by them for one’s darkest sides rather than just for one’s politeness and good manners.

- Highlight (yellow)

Sex in which two people can express their defiling urges is, for Proust, at heart an indication of a quest for complete acceptance. We know we can please others with our goodness, but – suggests Proust – what we really want is also to be endorsed for our more peculiar and dark impulses. The discipline involved in growing up into a good person seeks occasional alleviation, which is what sex can provide in those rare moments when two partners trust one another enough to reveal their otherwise strictly censored desires to dirty and insult. Though defiling sex seems on the surface to be about hurting another person, really it’s a quest for intimacy and love – and a delight that, for a time at least, we can be as bad as we like and still turn out to be the object of another’s affection.

- Highlight (yellow)

An affair is a love – or sexual – story between two people, one of whom(at least) is ostensibly committed to someone else. Most importantly, in our times, an affair is a disaster, pretty much the greatest betrayal that can befall us, a harbinger of untrammelled suffering, frequently the end of the relationship it has violated and almost always an occasion for fierce moralizing and the division of participants into goodies(who have been betrayed) and monsters(who have betrayed).

- Highlight (yellow)

Not restricted.

- Note

Affairs begin long before there is anyone to have an affair with. Their origins lie with certain initially minute fissures that open up within a subtly fracturing couple. The affair pre-dates, possibly by many years, the arrival of any actual lover.

- Highlight (yellow)

It is common to ask when a cataclysmic event such as, for example, the French Revolution began. A traditional response is to point to the summer of 1789, when some of the deputies at the Estates General took an oath to remain in session until a constitution had been agreed on, or a few days later when a group of Parisians attacked and broke into the Bastille prison. But a more sophisticated and instructive approach locates the beginning significantly earlier: with the bad harvests of the previous ten years, with the loss of royal prestige following military defeats in North America in the 1760s or with the rise of a new philosophy in the middle of the century that stressed the idea of citizens’ rights. At the time, these incidents didn’t seem particularly decisive; they didn’t immediately lead to major social change or reveal their solemn nature. But they slowly and powerfully put the country on course for the upheavals of 1789: they moved the country into a revolution-ready state. Likewise, affairs begin long before the meeting at the conference or the whispered confidences at the party. It is not key to fixate on the trip to Miami or the login details of the website. The whole notion of who is to blame and for what suddenly starts to look much more complicated and less clear cut. One should be focusing on certain conversations that didn’t go well in the kitchen three summers ago or the sulk in the taxi home five years before. The drama began long before anything dramatic unfolded. This is how some of the minute but real causes might be laid out by a partner who eventually strayed.

- Highlight (yellow)

rankles

- Highlight (yellow)

Continue nur to be painful; fester.

- Note

sanguine

- Highlight (yellow)

Cheerfully optimistic

- Note

subsidiary

- Highlight (yellow)

Less important but related.

- Note

diatribe

- Highlight (yellow)

Forceful and bitter verbal attack

- Note

intransigent,

- Highlight (yellow)

Unwilling to change one’s views

- Note

hector,

- Highlight (yellow)

Talk to someone in a bullying way.

- Note

Whatever its benefits and pains, being involved in an affair should, if nothing else, cure us once and for all of any tendency to moralize – that is, to look harshly and with strict judgement on the misdemeanours and follies of others.

- Highlight (yellow)

mendacity,

- Highlight (yellow)

Untruthfulness

- Note

histrionic

- Highlight (yellow)

Overly theatrical or melodramatic.

- Note

stymied

- Highlight (yellow)

Prevent or hinder the progess of.

- Note

Beneath the surface of almost every argument lies a forlorn attempt by two people to get the other to see, acknowledge and respond to their emotional reality and sense of justice. Beyond the invective is a longing that our partner should witness, understand and endorse some crucial element of our own experience.

- Highlight (yellow)

Abusive or highly critical language.

- Note

The tragedy of every sorry argument is that it is constructed around a horrific mismatch between the message we so badly want to send(‘I need you to love me, know me, agree with me’) and the manner in which we are able to deliver it(with impatient accusations, sulks, put-downs, sarcasm, exaggerated gesticulations and forceful ‘fuck you’s).

- Highlight (yellow)

Use gestures

- Note

A bad argument is a failed endeavour to communicate, which perversely renders the underlying message we seek to convey ever less visible.

- Highlight (yellow)

demented

- Highlight (yellow)

Driven to behave irationally.

- Note

Interminable

- Highlight (yellow)

Endless

- Note

Why should it be so hard to trace the origins of our rage? At points because what offends us is so humiliating in structure. It can be shameful for us to realize that the person in whom we have invested so much may not actually desire us physically, or may not fundamentally be kind, or could be exploiting us financially or gravely impeding our professional aspirations.

- Highlight (yellow)

diversionary

- Highlight (yellow)

An instance of turning something aside from its course.

- Note

When we’re on the receiving end of a difficult insight into our failings, what makes us bristle and deny everything isn’t generally the accusation itself(we know our flaws all too well), it’s the surrounding atmosphere. We know the other is right, we just can’t bear to take their criticism on board, given how severely it has been delivered.

- Highlight (yellow)

upbraiding

- Highlight (yellow)

Find fault with someone or scold.

- Note

Plato once outlined an idea of what he called the ‘just lie’. If a crazed person comes to us and asks, ‘Where’s the axe?’ we are entitled to lie and say we don’t know – because we understand that if we were to tell the truth they would probably use the tool to do something horrendous to us. That is, we can reasonably tell a lie when our life is in danger. In the same way, our partner might not literally be searching for an axe when they make their accusation, but psychologically this is precisely how we might experience them – which makes it understandable if we say we simply don’t know what they are talking about.

- Highlight (yellow)

What is so sad is how easily we the accused might, if only the circumstances were more sympathetic, confess to everything. We would in fact love to unburden ourselves and admit to what is broken and wounded in us. People don’t change when they are gruffly told what’s wrong with them; they change when they feel sufficiently supported to undertake the change they – almost always – already know is due.

- Highlight (yellow)

Abrupt or taciturn.

- Note

paroxysms

- Highlight (yellow)

A sudden attack or violent expression of a particular emotion or activity.

- Note

spluttering

- Highlight (yellow)

Make a series of short coughing or spitting sounds.

- Note

cretin.

- Highlight (yellow)

A stupid person.

- Note

imperturbable

- Highlight (yellow)

Unable to be upset or excited.

- Note

we should bear in mind that it is at least in theory entirely possible to be cruel, dismissive, stubborn, harsh and wrong – and keep one’s voice utterly steady. Just as one can, equally well, be red-nosed, whimpering and incoherent – and have a point.

- Highlight (yellow)

We need to keep hold of a heroically generous attitude: rage and histrionics can be the symptoms of a desperation that sets in when a hugely important intimate truth is being blatantly ignored or denied, with the uncontrolled person being neither evil nor monstrous.

- Highlight (yellow)

Obviously the method of delivery is drastically unhelpful; obviously it would always be better if we didn’t start to cry. But it is not beyond understanding or, hopefully, forgiveness if we were to do so.

- Highlight (yellow)

We should all have a little film of ourselves at our very worst moments from which we replay brief highlights and so remember that, while we looked mad, our contortions were only the outer signs of an inner agony at being unable to make ourselves understood on a crucial point by the person we relied on.

- Highlight (yellow)

day … Unfortunately, we don’t necessarily always tell our partner that we are causing problems because we are sad about things that have nothing to do with them; we just create arguments to alleviate our distress – we are mean to them because our boss didn’t care, the economy wasn’t available for a chat and there was no God to implore.

- Highlight (yellow)

Beg someone earnestly.

- Note

denunciations

- Highlight (yellow)

Condemnation of something.

- Note

lodestar

- Highlight (yellow)

A star used to guide a ship.

- Note

we should cease cynically lauding the idea of the normal when it suits us by acknowledging that almost everything that is beautiful and worth appreciating in our relationship is deeply un-normal. It’s very un-normal that someone should find us attractive, should have agreed to go out with us, should put up with our antics, should have come up with such an endearing nickname for us that alludes to our favourite animal from childhood, should have bothered to spend some of their weekend sewing on buttons for us – and should bother to listen to our anxieties late into the night. We are the beneficiaries of some extremely rare eventualities and it is the height of ingratitude to claim to be a friend of the normal when most of what is good in our lives is the result of awesomely minuscule odds.

- Highlight (yellow)

Foolish, outrageous, or amusing behavior.

- Note

badgering

- Highlight (yellow)

Pester; ask someone annoyingly and repeatedly for something.

- Note

phoney

- Highlight (yellow)

Not genuine; fraudulent.

- Note

filial

- Highlight (yellow)

Of or due from a son or daughter.

- Note

railroaded

- Highlight (yellow)

Cowed or coerced.

- Note

Their task as our partner isn’t to bully us into making confessions that we would have been ready to accept from the start, but to help us evolve away from the worst sides of people who have inevitably messed us up a little and yet whom we can’t – of course, despite everything – stop loving inordinately.

- Highlight (yellow)

The fear of heights is usually manifestly unreasonable: the balcony obviously isn’t about to collapse, there’s a strong iron balustrade between us and the abyss, the building has been repeatedly tested by experts. We may know all this intellectually, but it does nothing to reduce our sickening anxiety in practice. If a partner were patiently to begin to explain the laws of physics to us, we wouldn’t be grateful; we would simply feel they had misunderstood us. Much that troubles us has a structure akin to vertigo: our worry isn’t exactly reasonable, but we’re unsettled all the same. We can, for example, continue to feel guilty about letting down our parents, no matter how nice to them we’ve actually been. Or we can feel very worried about money, even if we’re objectively economically quite safe. We can feel horrified by our own appearance, even though no one else judges our face or body harshly. Or we can be certain that we’re failures who’ve messed up everything we’ve ever done, even if, in objective terms, we seem to be doing pretty well. We can obsess that we’ve forgotten to pack something, even though we’ve taken a lot of care and can in any case buy almost everything at the other end. Or we may feel that our life will fall apart if we have to make a short speech, even though thousands of people make quite bad speeches every day and their lives continue as normal.

- Highlight (yellow)

A railing supported by balusters, usually in the balcony.

- Note

phantasms,

- Highlight (yellow)

A figment of the imagination.

- Note

oblique

- Highlight (yellow)

Not specific or direct in addressing a point.

- Note

coax

- Highlight (yellow)

Persuade gradually through flattery.

- Note

frottage

- Highlight (yellow)

The practice of rubbing against the clothed body of another person as a means to achieve sexual gratification.

- Note

conciliator

- Highlight (yellow)

Stop someone from being angry or disconcerted.

- Note

paradigm

- Highlight (yellow)

A typical example or pattern of something; a model.

- Note

surmount

- Highlight (yellow)

Overcome something difficult.

- Note

recriminations,

- Highlight (yellow)

An accusation in response to one from someone.

- Note

The only people we can think of as profoundly admirable are those we don’t yet know very well.

- Highlight (yellow)

For many of us, love starts rapidly, often at first sight: with an overwhelming impression of the other’s loveliness. This phenomenon – the crush – goes to the heart of the modern understanding of love. It could seem like a small incident, a minor planet in the constellation of love, but it is in fact the underlying secret central sun around which our notions of the Romantic revolve. A crush represents in pure and perfect form the essential dynamics of Romanticism: the explosive interaction of limited knowledge, outward obstacles to further discovery and boundless hope.

- Highlight (yellow)

We wouldn’t be able to develop crushes if we weren’t so good at allowing a few details about someone to suggest the whole of them. From a few cues only, perhaps a distant look in the eyes, a forthright brow or a generous wit, we rapidly start to anticipate an intense connection and stretches of happiness, buoyed by profound mutual sympathy and understanding.

- Highlight (yellow)

the primary error of the crush is to ignore the fact that life will in important ways have twisted us all out of shape.

- Highlight (yellow)

malice)

- Highlight (yellow)

Bad intention.

- Note

Choosing whom to commit ourselves to is therefore merely a case of identifying a specific kind of dissatisfaction we can bear rather than an occasion to escape from grief altogether.

- Highlight (yellow)

Epochal

- Highlight (yellow)

Forming or characterizing an epoch.

- Note

The cure for unrequited love is, in structure, therefore very simple. We must get to know them better. The more we learn about them, the less they will ever look like the solution to our uneasy lives. We will discover the endless small ways in which they are irksome; we’ll get to know how stubborn, how critical, how cold and how hurt by things that strike us as meaningless they can be. That is, if we get to know them better, we will realize how much they have in common with everyone else.

- Highlight (yellow)

When we spot apparent perfection, we tend to blame our spectacular bad luck for the mediocrity of our lives, without realizing that we are mistaking an asymmetry of knowledge for an asymmetry of quality: we are failing to see that our partner, home and job are not especially awful, but rather that we know them especially well.

- Highlight (yellow)

extrapolate

- Highlight (yellow)

Extend the application of.

- Note

minutiae

- Highlight (yellow)

The small details of something

- Note

flashpoints

- Highlight (yellow)

A place or event where trouble flares up.

- Note

curt

- Highlight (yellow)

rudely brief.

- Note

rancour

- Highlight (yellow)

Biterness or resentfulness.

- Note

thrall

- Highlight (yellow)