Why Did Claude Monet Lov…

Metadata

- Author: @culturaltutor on Twitter

- Full Title: Why Did Claude Monet Lov…

- Category:tweets

- URL: https://twitter.com/culturaltutor/status/1588336446003634177

Highlights

- Why did Claude Monet love the colour blue so much?

Well, it all began with four friends and a mistake…

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - The year is 1862, and four young painters at the French Academy of Fine Arts called Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille, realised they had something in common.

Academic painting all took place in a studio, much like this:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - The four of them found it old-fashioned, unrealistic, and uninspiring.

The Academic style seemed artificial (carefully orchestrated lighting) and contrived (it imitated the Renaissance).

And the themes - of Biblical and Classical history or mythology - didn’t interest them.

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - So they starting painting outdoors (“en plein air” in French) and, led by the older artist Edouard Manet, embraced a wholly different form of realism.

Outside the studio, lighting and human figures were different. In Manet’s Balcony we can detect the start of this shift:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - Soon enough Paul Cezanne and Camille Pissarro joined them, and a movement was born.

They didn’t paint reality as a camera might capture it, but as the eye perceives it from one moment to the next with all its movement, changing light, sudden glimpses, fog, and blur:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - And they started to realise just how important colour was.

Even in Monet’s early works, like La Grenouillére (1869), we can see this in action. Up close there is no “form” as there was in Academic painting, but from a distance those splashes of colour unite to create reality:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - And then, as Renoir said, “one morning, one of us ran out of black, and it was the birth of Impressionism.”

This was the big leap: from the black shadows of Academicism to the blue shadows of Impressionism.

Their paintings suddenly had an extraordinary brightness and vividity:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - After all, no shadow is truly black; it comprises a mixture of tones and colours.

And blue is the ultimate shade of the outdoors, being the colour of the sky and from there permeating everything else with its tones, even snow.

Consider Monet’s The Magpie and its shadows:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - But Monet would take this further than anybody else, not only casting his work through a subtle lens of natural blue brightness, but diving headlong into the world of shifting colours and into the fundamental “blueness” of the outdoors.

Like the London fog, say:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - Or the Venetian Grand Canal, the river Seine, the cathedral of Rouen, or the poplars of Normandy.

Another technique the Impressionists adopted was the use of brighter canvasses. Normally they were dark grey, but by the end Monet and co were using white canvasses.

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - When we think of a painter, one of the first images that comes to mind is a scruffy looking figure sitting outdoors with an easel, palette, and bundle of brushes.

That stereotype was created by the Impressionists, as in Manet’s touching painting of Claude Monet at Argenteuil:

(View Tweet)

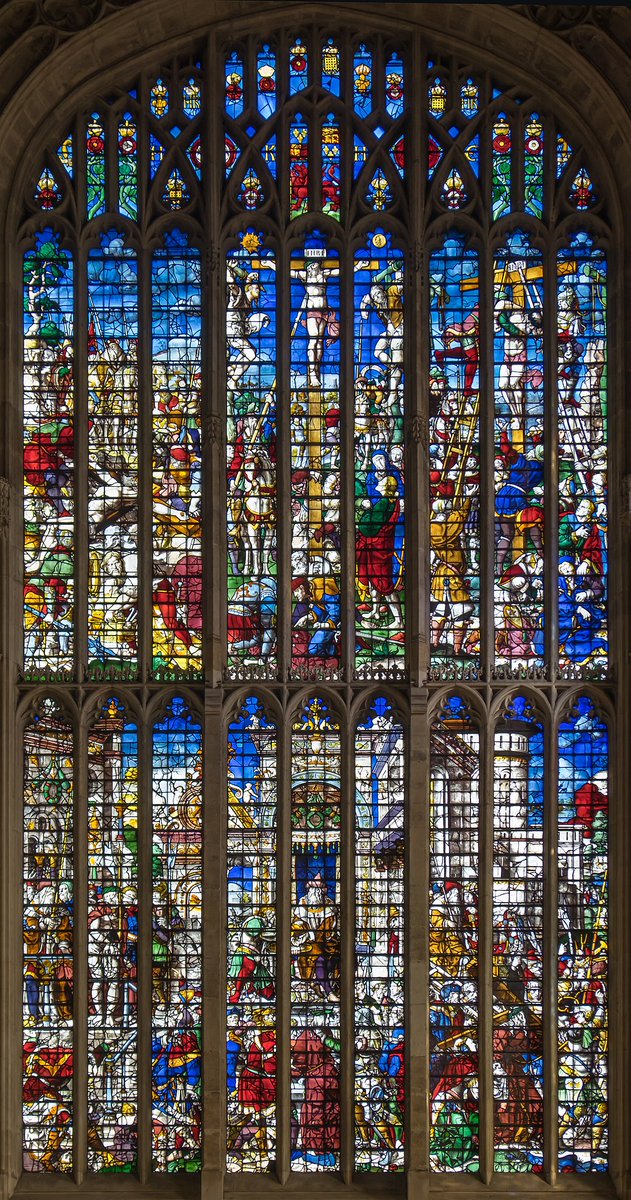

(View Tweet) - Now, it goes without saying that blue had been used in art before the birth of Claude Monet.

The Ancient Egyptians had done so, and it also crops up in Medieval art, like the Wilton Diptych, and especially in stained glass:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - In the 16th century it was painters of the Venetian School like Titian, more so than the Florentine masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, who used blue with real intensity.

And, after him, by Baroque artists like Guido Reni:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - But the most intense blue pigment had long been ultramarine, produced from lapis lazuli, which was very expensive.

Hence painters like Johannes Vermeer only used it sparingly, for particular and vivid effect:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - Then, in 1709 the intense Prussian Blue was invented; in 1789 came Cerulean Blue; in 1803 Cobalt Blue. These were cheaper and equally as vivid. Thanks to technology, the colour blue could now be truly unleashed.

Thomas Gainsborough painted the famous Blue Boy with Prussian Blue:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - And, it should be mentioned, the Impressionists didn’t actually invent painting “en plein air”.

A French group known as the “Barbizon School” had innovated painting outdoors in the 1830s. But their priority, led by Courbet and Millet, had been a form of social realism:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - And nor were they first to paint ordinary, non-classical subjects.

There had been a long tradition in Northern European art, especially during the Dutch Golden Age, of depicting moments from every day life, whether household or landscape scenes:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - Another huge influence on the Impressionists was the influx of Japanese prints into Europe, both because of their style and colour.

Prussian Blue had proven a popular colour in Japan, where masters like Hiroshige and Hokusai used it for their skies and oceans.

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - But that’s the story of art. One person or group innovates, and another takes that innovation to its fullest potential. The Impressionists united all these themes, ideas, styles, and - inspired by their firm opposition to Academicism - created something new. (View Tweet)

- And it was Monet, more than any of his contemporaries, who fully immerged himself in the colour of Impressionism, the colour of the outdoors: blue.

In his early works, perhaps before the “mistake” Renoir mentioned, Monet’s blue was less characteristic:

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - But, by his late career, we find the Monet so well-known, so well-loved.

Blueness has descended, filtered through snow and sunlight and haze, and the world has splintered into brush-strokes of colour.

Impressionism had, perhaps, found its highest form.

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - He travelled to London and Venice, taking that style with him, and painted those cities in ways that, far from what a photograph would capture, seem to contain something truer about them, about how they feel to see, the impression they leave…

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - And, of course, in his beloved garden, where Monet bequeathed an artistic gift to the world with his two hundred and fifty paintings of water-lilies.

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - And here is Claude Monet himself, one of the most enduringly popular painters of our time, photographed with the bridge and pond made famous by his work, and, as he surely so loved, en plein air…

(View Tweet)

(View Tweet) - If you enjoyed this journey through the works of Claude Monet you may also like my free newsletter, Areopagus. It features seven short topics every Friday, including art, architecture, history, and rhetoric: Consider joining 45k+ other readers here: https://t.co/xicFtTsZ6h (View Tweet)