How Can We Develop Transformative Tools for Thought?

Metadata

- Author: Andy Matuschak

- Full Title: How Can We Develop Transformative Tools for Thought?

- Category:articles

- Published Date: 2019-10-12

- Document Note: According to the document, a mnemonic medium is a new type of tool for thought that is designed to make it almost effortless for users to remember what they read. It is still in its early days and has many deficiencies that need improvement. The document suggests that the mnemonic medium is genuinely helping people remember and is exponentially increasing efficiency, meaning the more people study, the more benefit they get per minute studied. The mnemonic medium is designed to largely automate away the problem of memory, making it easier for people to spend more time focusing on other parts of learning, such as conceptual issues. The document also discusses the importance of memory and the challenges of identifying what information is beneficial to memorize. The overall theme of the document is about developing transformative tools for thought. Based on the passage provided, a mnemonic medium is a specific type of tool for thought that is designed to augment human memory, while a tool for thought can encompass a broader range of cognitive functions. The document is about developing transformative tools for thought, including the mnemonic medium and other ideas such as mnemonic video and executable books. However, the document does not provide a detailed comparison between a mnemonic medium and a tool for thought beyond the fact that a mnemonic medium is a specific type of tool for thought designed for memory augmentation.

- Document Tags: Tools for Thought

- Summary: The essay explores the idea of developing transformative tools for thought, focusing on the mnemonic medium as an experimental prototype system that can augment human memory. The mnemonic medium aims to make it almost effortless for users to remember what they read, creating a powerful immersive context that enables new kinds of thought. The essay also touches on other tools for thought and the challenges of developing such tools in the tech industry. The work is about exploring an open-ended question of how to develop tools that change and expand the range of thoughts human beings can think.

- URL: https://numinous.productions/ttft/

Highlights

- tools for thought (View Highlight)

- Note: “Tools to augment human intelligence.”

- pay lip service to (View Highlight)

- Note: From Oxford Dictionary: “express approval of or support for (something) without taking any significant action.” “They pay lip service to equality but they don’t want to do anything about it”

- A word on nomenclature: the term “tools for thought” rolls off neither the tongue nor the keyboard. What’s more, the term “tool” implies a certain narrowness. Alan Kay has argued that a more powerful aim is to develop a new medium for thought. A medium such as, say, Adobe Illustrator is essentially different from any of the individual tools Illustrator contains. Such a medium creates a powerful immersive context, a context in which the user can have new kinds of thought, thoughts that were formerly impossible for them. Speaking loosely, the range of expressive thoughts possible in such a medium is an emergent property of the elementary objects and actions in that medium. If those are well chosen, the medium expands the possible range of human thought. (View Highlight)

- A word on nomenclature: the term “tools for thought” rolls off neither the tongue nor the keyboard. What’s more, the term “tool” implies a certain narrowness. Alan Kay has argued that a more powerful aim is to develop a new medium for thought. A medium such as, say, Adobe Illustrator is essentially different from any of the individual tools Illustrator contains. Such a medium creates a powerful immersive context, a context in which the user can have new kinds of thought, thoughts that were formerly impossible for them. Speaking loosely, the range of expressive thoughts possible in such a medium is an emergent property of the elementary objects and actions in that medium. If those are well chosen, the medium expands the possible range of human thought. (View Highlight)

- Let’s come back to that phrase from the opening, about changing “the thought patterns of an entire civilization”. It sounds ludicrous, a kind of tech soothsaying. Except, of course, such changes have happened multiple times during human history: the development of language, of writing, and our other most powerful tools for thought. And, for better and worse, computers really have affected the thought patterns of our civilization over the past 60 years, and those changes seem like just the beginning (View Highlight)

- Note: This, I think, is why “memes” and “internet humor” are a thing.

- for better and worse, computers really have affected the thought patterns of our civilization over the past 60 years, and those changes seem like just the beginning (View Highlight)

- The musician and comedian Martin Mull has observed that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture”. (View Highlight)

- Note: This reminds me of an episode form Cal Newport’s podcast: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2YhSnjfC9ZGbtH880MLeHD?si=pQNqgRIIQZinfB0At0Ef1A

- The more transformative the tool, the larger the gap that is opened. Conversely, the larger the gap, the more difficult the new tool is to evoke in writing. But what writing can do, and the reason we wrote this essay, is act as a bootstrap. (View Highlight)

- Note: Think more about this. Something something about leverage.

- Aspirationally, the mnemonic medium makes it almost effortless for users to remember what they read. (View Highlight)

- Is it possible to design a new medium which much more actively supports memorization? That is, the medium would build in (and, ideally, make almost effortless) the key steps involved in memory. If we could do this, then instead of memory being a haphazard event, subject to chance, the mnemonic medium would make memory into a choice. (View Highlight)

- how could you build a medium to better support a person’s memory of what they read? What interactions could easily and enjoyably help people consolidate memories? And, more broadly: is it possible to 2x what people remember? 10x? And would that make any long-term difference to their effectiveness? (View Highlight)

- Of course, for long-term memory it’s not enough for users to be tested just once on their recall. Instead, a few days after first reading the essay, the user receives an email asking them to sign into a review session. In that review session they’re tested again, in a manner similar to what was shown above. Then, through repeated review sessions in the days and weeks ahead, people consolidate the answers to those questions into their long-term memory. (View Highlight)

- The highlighted time interval is the duration until the user is tested again on the question. Questions start out with the time interval “in-text”, meaning the user is being tested as they read the essay. That rises to five days, if the user remembers the answer to the question. The interval then continues to rise upon each successful review, from five days to two weeks, then a month, and so on. After just five successful reviews the interval is at four months. If the user doesn’t remember at any point, the time interval drops down one level, e.g., from two weeks to five days. (View Highlight)

- This takes advantage of a fundamental fact about human memory: as we are repeatedly tested on a question, our memory of the answer gets stronger, and we are likely to retain it for longer The literature on this effect is vast. (View Highlight)

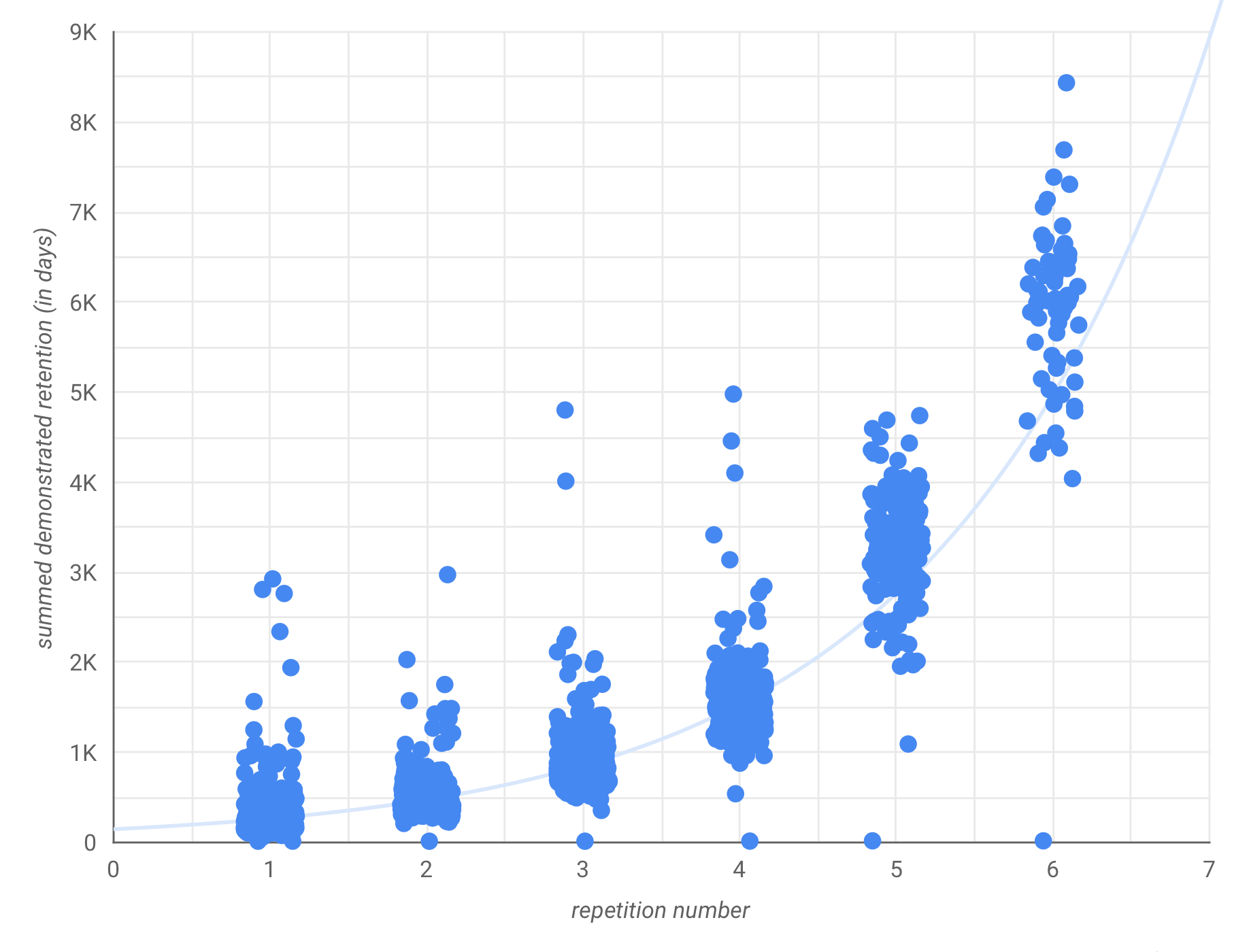

- Although it’s early days for Quantum Country we can begin to see some of the impact of the mnemonic medium. Plotted below is the demonstrated retention of answers for each user, versus the number of times each question in the mnemonic essay has been reviewed:

The graph takes a little unpacking to explain. By a card’s “demonstrated retention” we mean the maximum time between a successful review of that card, and the prior review of that card. A little more concretely, consider repetition number 6, say (on the horizontal axis). At the point, a user has reviewed all 112 questions in the essay 6 times. And the vertical axis shows the total demonstrated retention, summed across all cards, with each blue dot representing a single user who has reached repetition 6.

So, for instance, after 6 repetitions, we see from the graph that most users are up around 6,000 days of demonstrated retention. That means an average of about 6,000 / 112 ~ 54 days per question in the essay. Intuitively, that seems pretty good – if you’re anything like us, a couple of months after reading something you have only a hazy memory. By contrast, these users have, at low time cost to themselves (of which more below), achieved nearly two months of demonstrated retention across 112 detailed questions. (View Highlight)

The graph takes a little unpacking to explain. By a card’s “demonstrated retention” we mean the maximum time between a successful review of that card, and the prior review of that card. A little more concretely, consider repetition number 6, say (on the horizontal axis). At the point, a user has reviewed all 112 questions in the essay 6 times. And the vertical axis shows the total demonstrated retention, summed across all cards, with each blue dot representing a single user who has reached repetition 6.

So, for instance, after 6 repetitions, we see from the graph that most users are up around 6,000 days of demonstrated retention. That means an average of about 6,000 / 112 ~ 54 days per question in the essay. Intuitively, that seems pretty good – if you’re anything like us, a couple of months after reading something you have only a hazy memory. By contrast, these users have, at low time cost to themselves (of which more below), achieved nearly two months of demonstrated retention across 112 detailed questions. (View Highlight) - This is the big, counterintuitive advantage of spaced repetition: you get exponential returns for increased effort. On average, every extra minute of effort spent in review provides more and more benefit. This is in sharp contrast with most experiences in life, where we run into diminishing returns. For instance, ordinarily if you increase the amount of time you spend reading by 50%, you expect to get no more than 50% extra out of it, and possibly much less. But with the mnemonic medium when you increase the amount of time you spend reading by 50%, you may get 10x as much out of it. Of course, we don’t quite mean those numbers literally. But it does convey the key idea of getting a strongly non-linear return. It’s a change in the quality of the medium. (View Highlight)

- This delayed benefit makes the mnemonic medium unusual in multiple ways. Another is this: most online media use short-term engagement models, using variations on operant conditioning to drive user behavior. This is done by Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and many other popular media forms. The mnemonic medium is much more like meditation – in some ways, the anti-product, since it violates so much conventional Silicon Valley wisdom – in that the benefits are delayed, and hard to have any immediate sense of. (View Highlight)

- we also need to step back and think more skeptically about questions such as: is this medium really working? What effect is it actually having on people? Can it be made 10x better? 100x better? Or, contrariwise, are there blockers that make this an irredeemably bad or at best mediocre idea? How important a role does memory play in cognition, anyway? (View Highlight)

- Of course, this kind of feedback and these kinds of results should be taken with a grain of salt. The mnemonic medium is in its early days, has many deficiencies, and needs improvement in many ways (of which more soon). (View Highlight)

- Note: Which deficiencies, in particular?

- Quantum Country is an example of a memory system. That is, it’s a system designed to help users easily consolidate what they’ve learned into long-term memory. (View Highlight)

- At a minimum, it seems likely the mnemonic medium is genuinely helping people remember. And furthermore it has the exponentially increasing efficiency described above: the more people study, the more benefit they get per minute studied. (View Highlight)

- In modern times, many memory systems have been developed. Among the better known are Anki, SuperMemo, Quizlet, Duolingo, and Memrise. (View Highlight)

- Like Quantum Country, each of these systems uses increasing time intervals between reviews of particular questions. Such systems are sometimes known as spaced-repetition memory systems (or SRM systems) (View Highlight)

- SRM systems are most widely used in language learning. Duolingo, for instance, claims 25 million monthly active users. Reports are mixed on success. Some serious users are enthusiastic about their success with Duolingo. But others find it of limited utility. The company, of course, touts research showing that it’s incredibly successful. (View Highlight)

- It seems likely to us that Duolingo and similar systems are useful for many users as part of (but only part of) a serious language learning program (View Highlight)

- Note: What does this part mean?

- One of the ideas motivating Quantum Country is that memory systems aren’t just useful for simple declarative knowledge, such as vocabulary words and lists of capitals. In fact, memory systems can be extraordinarily helpful for mastering abstract, conceptual knowledge, the kind of knowledge required to learn subjects such as quantum mechanics and quantum computing. (View Highlight)

- narrative embedding makes it possible for context and understanding to build in ways difficult in other memory systems. (View Highlight)

- Other people have also developed ways of using memory systems for abstract, conceptual knowledge. Perhaps most prominently, the creator of the SuperMemo system, Piotr Wozniak, has written extensively about the many ingenious ways he uses memory systems (View Highlight)

- in Quantum Country an expert writes the cards, an expert who is skilled not only in the subject matter of the essay, but also in strategies which can be used to encode abstract, conceptual knowledge. And so Quantum Country provides a much more scalable approach to using memory systems to do abstract, conceptual learning. (View Highlight)

- Note: Andy writes this comparison with SuperMemo, a case which he describes as something along the lines of (non-verbatim): “Written by experts, for the experts.” Quantum Country, he says, is written by experts for beginners, in some sense (at least that’s what I understand).

- While a medium may be simple, that doesn’t mean it’s not profound. As we shall see, the mnemonic medium has many surprising properties. It turns out that flashcards are dramatically under-appreciated, and it’s possible to go much, much further in developing the mnemonic medium than is a priori obvious. (View Highlight)

- Existing memory systems barely scratch the surface of what is possible. We’ve taken to thinking of Quantum Country as a memory laboratory. That is, it’s a system which can be used both to better understand how memory works, and also to develop new kinds of memory system. We’d like to answer questions such as: • What are new ways memory systems can be applied, beyond the simple, declarative knowledge of past systems? • How deep can the understanding developed through a memory system be? What patterns will help users deepen their understanding as much as possible? • How far can we raise the human capacity for memory? And with how much ease? What are the benefits and drawbacks? • Might it be that one day most human beings will have a regular memory practice, as part of their everyday lives? Can we make it so memory becomes a choice; is it possible to in some sense solve the problem of memory? (View Highlight)

- cards are fundamental building blocks of the mnemonic medium, and card-writing is better thought of as an open-ended skill. Do it poorly, and the mnemonic medium works poorly. Do it superbly well, and the mnemonic medium can work very well indeed. By developing the card-writing skill it’s possible to expand the possibilities of the medium. (View Highlight)

- Most questions and answers should be atomic (View Highlight)

- It seemed that the more atomic questions brought more sharply into focus what he was forgetting, and so provided a better tool for improving memory. (View Highlight)

- Avoid orphan cards: These are cards which don’t connect closely to anything else. (View Highlight)

- When we first described Quantum Country above we explained it using a simple model of spaced repetition: increased consolidation strength for memories leading to increased time intervals between reviews. This is a helpful simple model, but risks creating the misleading impression that it’s all that’s going on in the system. In fact, for the mnemonic medium to work effectively, spaced repetition must be deployed in concert with many other ideas. The three ideas we just described – atomicity of questions and answers, making early questions trivial, avoiding orphan cards – are just three of dozens of important ideas used in the mnemonic medium. We won’t enumerate all those other ideas here – that’s not the purpose of this essay. But we want to emphasize this point, since it’s common for people to have the simplistic model “good memory system = spaced repetition”. That’s false, and an actively unhelpful way of thinking. (View Highlight)

- Note: A disclaimer on the importance of diving deeper into the details of learning using a mnemonic medium. It’s unhelpful to think spaced repetition = good memory; there are a bunch of nuances that we should always be aware of.

- Indeed, thinking in this way is one reason spaced-repetition memory systems often fail for individuals. We often meet people who say “Oh, I thought spaced repetition sounded great, and I tried Anki [etc], but it doesn’t work for me”. Dig down a little, and it turns out the person is using their memory system in a way guaranteed to fail. They’ll be writing terrible questions, or using it to learn a subject they don’t care about, or making some other error. They’re a little like a person who thinks “learning the guitar sounds great”, picks it up for half an hour, and then puts it down, saying that they sound terrible and therefore it’s a bad instrument. (View Highlight)

- said, we want to build as much support as possible into the medium. Ideally, even novices would benefit tremendously from the mnemonic medium. That means building in many ideas that go beyond the simplistic model of spaced repetition. (View Highlight)

- How can we ensure users don’t just learn surface features of questions? One question in Quantum Country asks: “Who has made progress on using quantum computers to simulate quantum field theory?” with the answer: “John Preskill and his collaborators”. This is the only “Who…?” question in the entire essay, and many users quickly learn to recognize it from just the “Who…?” pattern, and parrot the answer without engaging deeply with the question. This is a common failure mode in memory systems, and it’s deadly to understanding. (View Highlight)

- How to best help users when they forget the answer to a question? Suppose a user can’t remember the answer to the question: “Who was the second President of the United States?” Perhaps they think it’s Thomas Jefferson, and are surprised to learn it’s John Adams. In a typical spaced-repetition memory system this would be dealt with by decreasing the time interval until the question is reviewed again. But it may be more effective to follow up with questions designed to help the user understand some of the surrounding context. E.g.: “Who was George Washington’s Vice President?” (A: “John Adams”). Indeed, there could be a whole series of followup questions, all designed to help better encode the answer to the initial question in memory. (View Highlight)

- How to encode stories in the mnemonic medium? People often find certain ideas most compelling in story form. Here’s a short, fun example: did you know that Steve Jobs actively opposed the development of the App Store in the early days of the iPhone? It was instead championed by another executive at Apple, Scott Forstall. Such a story carries a force not carried by declarative facts alone. It’s one thing to know in the abstract that even the visionaries behind new technologies often fail to see many of their uses. It’s quite another to hear of Steve Jobs arguing with Scott Forstall against what is today a major use of a technology Jobs is credited with inventing. Can the mnemonic medium be used to help people internalize such stories? To do so would likely violate the principle of atomicity, since good stories are rarely atomic (though this particular example comes close). Nonetheless, the benefits of such stories seem well worth violating atomicity, if they can be encoded in the cards effectively. (View Highlight)

- The mnemonic medium is not a fixed form, but rather a platform for experimentation and continued improvement. (View Highlight)

- We said above that it’s a mistake to use the simplistic model “good memory system = spaced repetition”. In fact, while spaced repetition is a helpful way to introduce Quantum Country, we certainly shouldn’t pigeonhole the mnemonic medium inside the paradigm of existing SRM systems. Instead, it’s better to go back to first principles, and to ask questions like: what would make Quantum Country a good memory system? Are there other powerful principles about memory which we could we build into the system, apart from spaced repetition? (View Highlight)

- Note: verb. pigeonhole: to a particular category or class, especially in a manner that is too rigid or exclusive: “a tendency to pigeonhole him as a photographer and neglect his work in sculpture and painting”

- elaborative encoding. Roughly speaking, this is the idea that the richer the associations we have to a concept, the better we will remember it. As a consequence, we can improve our memory by enriching that network of associations. (View Highlight)

- In 1971, the psychologist Allan Paivio proposed the dual-coding theory, namely, the assertion that verbal and non-verbal information are stored separately in long-term memory. (View Highlight)

- Paivio and others investigated the picture superiority effect, demonstrating that pictures and words together are often recalled substantially better than words alone (View Highlight)

- In 1978, the psychologists Steven Smith, Arthur Glenberg, and Robert Bjork Steven M. Smith, Arthur Glenberg, and Robert A. Bjork, Environmental context and human memory (1978). reported several experiments studying the effect of place on human memory. In one of their experiments, they found that studying material in two different places, instead of twice in the same place, provided a 40% improvement in later recall. (View Highlight)

- When we discuss memory systems with people, many immediately respond that we should look into mnemonic techniques. This is an approach to memory systems very different to Quantum Country, Duolingo, Anki, and the other systems we’ve discussed. You’re perhaps familiar with simple mnemonic techniques from school. One common form is tricks such as remembering the colors of the rainbow as the name Roy G. Biv (red, orange, yellow, green, etc). Or remembering the periodic table of elements using a songAn enjoyable extended introduction to such techniques may be found in Joshua Foer’s book “Moonwalking with Einstein” (2012). (View Highlight)

- Note: A mnemonic technique is different from a mnemonic medium. A technique (from what I understand now) is to aid memory through some fancy little trick. One example mentioned in this article is remembering the colors of the rainbow through “Roy G. Biv.”

- A more complex variation is visualization techniques such as the method of loci. Suppose you want to remember your shopping list. To do so using the method of loci, you visualize yourself in some familiar location – say, your childhood home. And then you visualize yourself walking from room to room, placing an item from your shopping list prominently in each room. When you go shopping, you can recall the list by imagining yourself walking through the house – your so-called memory palace – and looking at the items in each room (View Highlight)

- When people respond to the mnemonic medium with “why do you focus on all that boring memory stuff?”, they are missing the point. By largely automating away the problem of memory, the mnemonic medium makes it easier for people to spend more time focusing on other parts of learning, such as conceptual issues. (View Highlight)

- a surprising number of people say they are “repulsed”, or some similarly strong word, by spaced-repetition memory systems. Their line of argument is usually some variant on: it is claimed that spaced-repetition systems help with memory; if that is true I must use the systems; but I hate using the systems. The response is to deny the first step of the argument. Of course, the mistake is elsewhere: there is absolutely no reason anyone “should” use such systems, even if they help with memory. Someone who hates using them should simply choose not to do so. Using memory systems is not a moral imperative! (View Highlight)

- We’ve met many mathematicians and physicists who say that one reason they went into mathematics or physics is because they hated the rote memorization common in many subjects, and preferred subjects where it is possible to derive everything from scratch. But in conversation it quickly becomes evident that they have memorized an enormous number of concepts, connections, and facts in their discipline. It’s fascinating these people are so blind to the central role memory plays in their own thinking.. It seems plausible, though needs further study, that the mnemonic medium can help speed up the acquisition of such chunks, and so the acquisition of mastery. (View Highlight)

- memory is not an end-goal in itself. It’s embedded in a larger context: things like creative problem-solving, problem-finding, and all the many ways there are of taking action in the world. (View Highlight)

- the most powerful tools for thought express deep insights into the underlying subject matter. (View Highlight)

- conventional tech industry product practice will not produce deep enough subject matter insights to create transformative tools for thought. Indeed, that’s part of the reason there’s been so little progress from the tech industry on tools for thought. This sounds like a knock on conventional product practice, but it’s not. That practice has been astoundingly successful at its purpose: creating great businesses. But it’s also what Alan Kay has dubbed a pop culture, not a research culture. To build transformative tools for thought we need to go beyond that pop culture. (View Highlight)